This weekend I watched Top Gun 2. Good movie, nothing on the original, but a great soundtrack, specifically the Kenny Loggins song: ‘highway to the danger zone’. Because I spend quite a lot of time thinking about markets, it reminded me of the bear market rally we’ve been in since October last year. It’s not a rally we bought into, literally or intellectually. The song also brought-to-mind the concept of a ‘death zone’. In mountaineering parlance, the death zone refers to altitudes above a certain point where the pressure of oxygen is insufficient to sustain human life. That’s where we are today.

Continuing the cinematic analogy, I developed a little narrative to help describe the current market outlook. Picture the scene… a group of tired climbers (investors), recently replenished with the remaining oxygen tanks (Chinese and Japanese central bank liquidity), mount a final summit attempt (new bull market) at the very end of the climbing season (storm clouds rolling in, aka the growing recessionary headwinds). Anyone who has seen any of the mountaineering movies on Netflix will get the picture. For those that haven’t.. it rarely ends well.

Let’s end the analogy, which risks oversimplification, and discuss some of the detail. The first thing to say is just how bad can it be given the economic data has held up quite well? That’s true, with a clear pick-up in US activity, for example, since the start of the year. Specifics include the bumper non-farm payroll surprise, with more than half a million new jobs added in January (and better than expected numbers in February), alongside a clear rebound in retail sales and personal consumption expenditures.

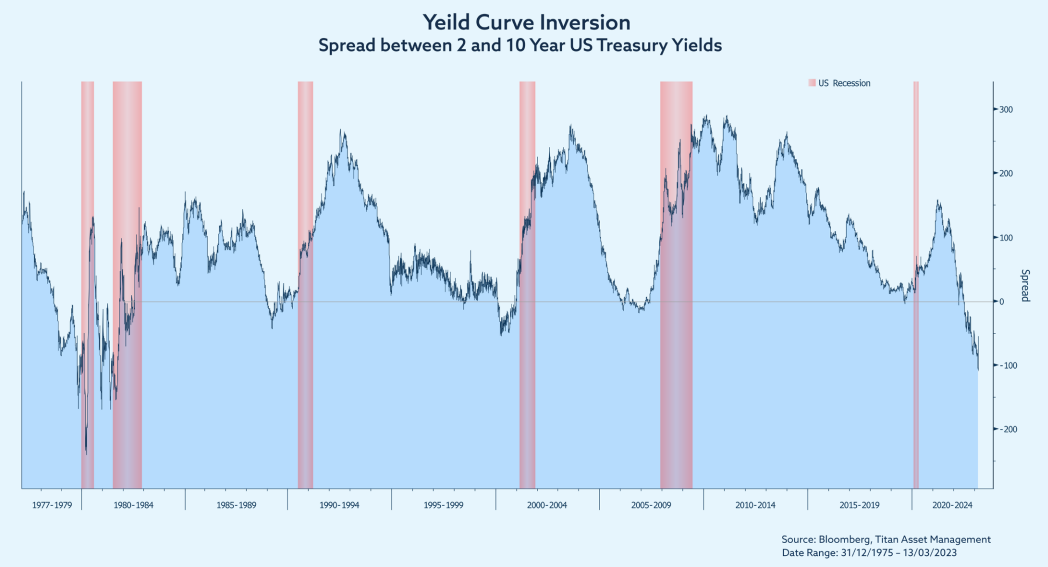

The issue is that good-news-is-now-bad-news for the economy and markets. With the economy running hotter than the Fed would like, inflation remains a problem. Last week Jerome Powell communicated that interest rates are ‘likely to be higher’ than previously anticipated, and they’ve already come a long way. It seems one policy error (excessive monetary loosening) is now being followed by excessive tightening. We are yet to feel the full shock of the near vertical increase in interest rates over the last year and higher-for-longer is in itself a form of tightening.

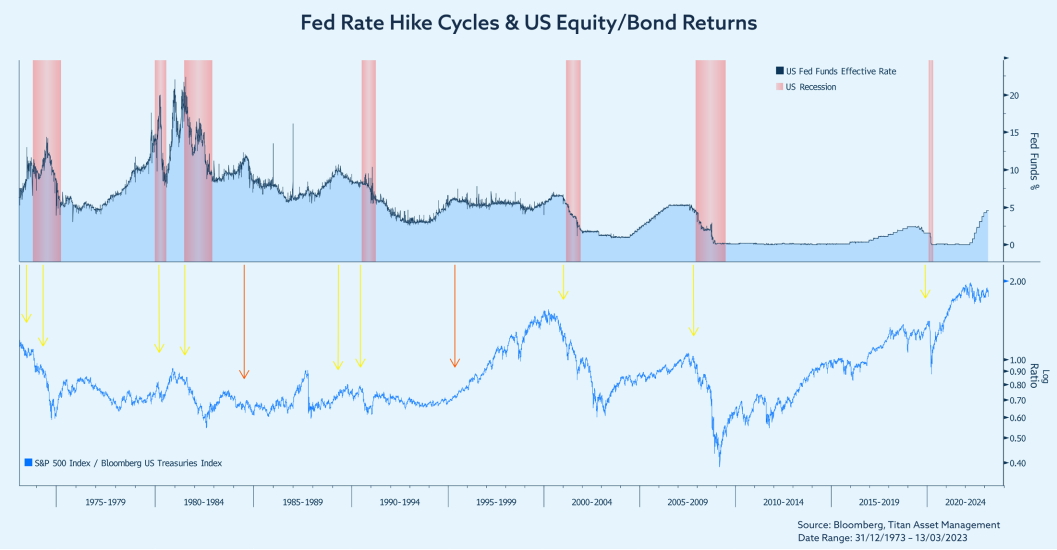

History tells us that this typically leads to recession. Despite the recent enthusiasm around resilient equity and credit markets, resulting in a plethora of soft or no-landing calls, it is extremely difficult to engineer a soft landing. This is shown by the red bars in the top panel of the below chart. In most cases US equities have gone on to underperform bonds, as shown by the blue line in the bottom panel of the same chart. To add some narrative, one pre-Covid historical example includes Alan Greenspan hiking rates from June 1999 to May 2000. Whilst equities almost reached a record high in September 2000, it wasn’t until the Fed started cutting rates in January 2001, alongside the onset of recession, that equity markets sold off.

Another example is when Greenspan started hiking rates in June 2004, taking the Fed Funds rate to 5.25% in June 2006. Given the more measured pace, the market continued to rally until October 2007 before finally falling over, just as the Fed started cutting interest rates, and before the start of an official recession. The subsequent bear market lasted until March 2009, 3 months after the last rate cut and 3 months before recession officially ended.

We think this is all to come but this is primarily a process, rather than an event, as households and businesses are impacted at different times as debt becomes due, and economic decisions are reset and made anew. I’m talking about houses that are not bought because of affordability, rents dropped or not taken-up for the same reason (hotel of mum and dad), declining discretionary spending due to extortionate interest on unpaid credit balances and car lease payments, VC investments put on hold due to declining expected profitability… and so on.

Speaking of VC investments, I say ‘primarily’, because an event of some description is also very possible. Silicon Valley Bank is a case in point. Yes, there are rules to mitigate these risks, and yes Silicon Valley Bank and other ‘smaller’ banks were excused due to US specific lobbying, but ultimately this points to underlying fragility and there is real concern about these fears spreading to other regional banks.

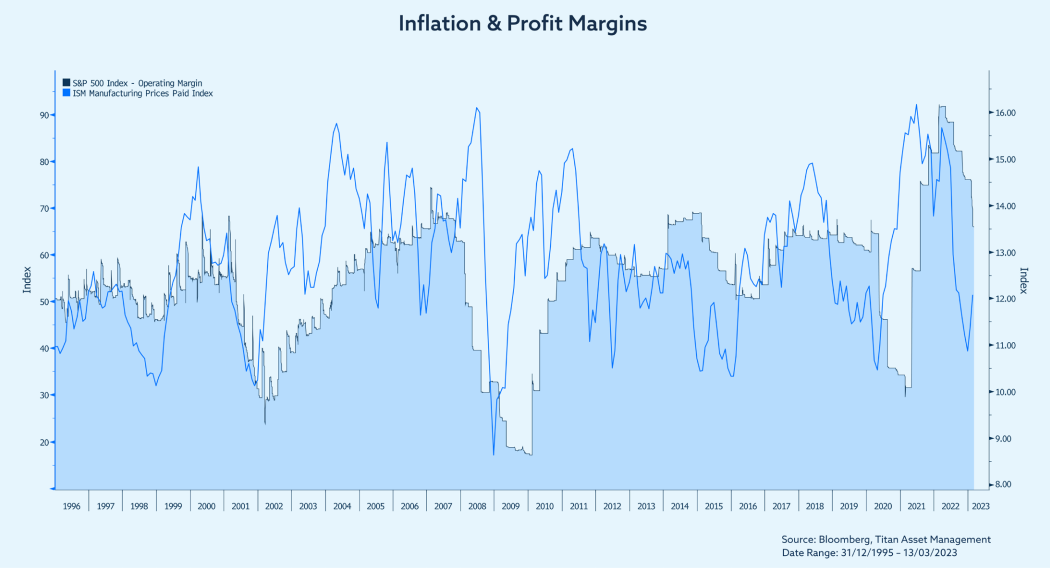

Banks, which are losing deposits to money market funds, will need to increase deposit rates to stem these flows, which will increase their cost of capital. The next domino to fall is real estate, with commercial office rents also showing signs of fragility. As accidents pile-up we will see further ripple-effects across the economy as the lagged impact of prior tightening starts to show its face. Equity markets aren’t trading on earnings. The primary driver is the inflation and employment data and the expected impact on the Fed response function. But once we reach a terminal rate, earnings will eventually re-assert themselves.

Corporate profit margins are deteriorating, and the impending earnings recession will hit hiring. With US equity valuations as high as they are, should corporate earnings merely revert to the historical mean, equities can drop noticeably and just because equities are resilient right now, it doesn’t mean they will be going forward.

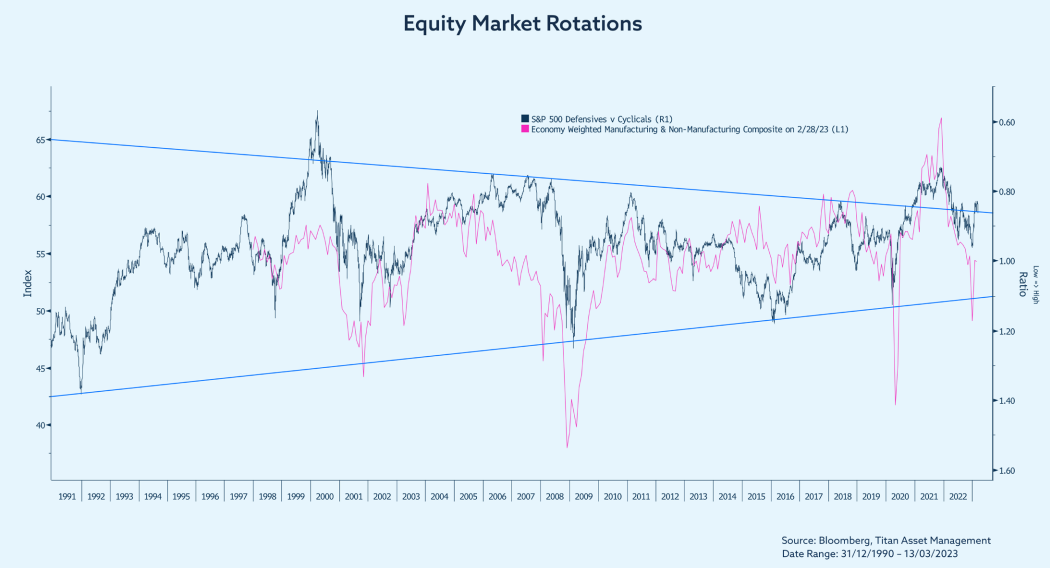

Another way to demonstrate this vulnerability is to look at the dramatic rotation, under the surface, across US equity sectors. This is demonstrated in the following chart which shows how cyclical stocks (those most geared to the economy) have outperformed defensives since the start of the year. The recent price action is statistically significant, unwinding around half the prior full year outperformance, and not backed by the fundamentals. We see this as a key risk with 30% downside in the ratio in the scenario where the S&P 500 falls to 3,000, our bear case scenario.

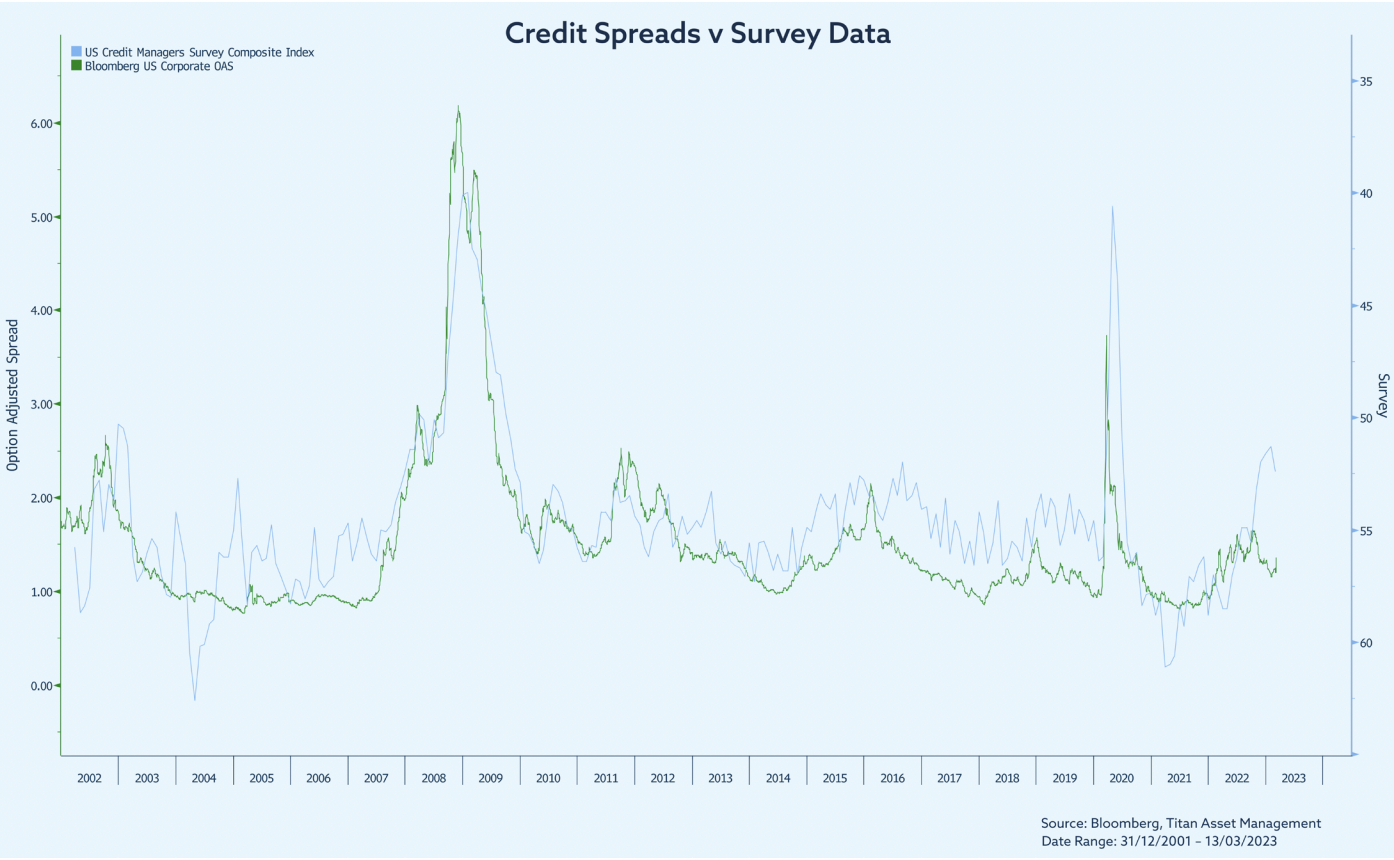

Part of the resilience in equities comes from credit markets. The disconnect is evident here as well given spreads remain tight despite the deteriorating US credit manager survey.

So where does that leave us? This is not the time to be mounting a fresh summit attempt. The thing about Everest, given the curvature of the terrain, is the summit is never in sight. It’s always just ahead.

Climbers, giddy on restocked oxygen, have persuaded themselves they can both summit and descend safely. But the climbing window is closing, and the storm clouds are rolling-in. We recommend heading down to base camp because now is the time to exercise sound risk management.

Bottom line, the old adage, “it’s not about timing the market, but time in the market”, has proven true over the years. When staying invested throughout the market cycle, there are other destinations and opportunities to explore. Cash now offers an attractive yield, as do bonds, which may come back in vogue later this year as inflation rolls over and the recessionary narrative picks-up place.

Within the US we retain a preference for defensive sectors and quality companies whilst outside the US we like Asia given attractive valuations and relative economic growth forecasts. We will be writing about this and more in our upcoming Quarterly Perspectives publication.

Bumpy start – January CIO commentary

It’s been a volatile start to 2022. For the last two-ish years, markets have enjoyed a buy-the-dip mentality as pro-growth fiscal and […]