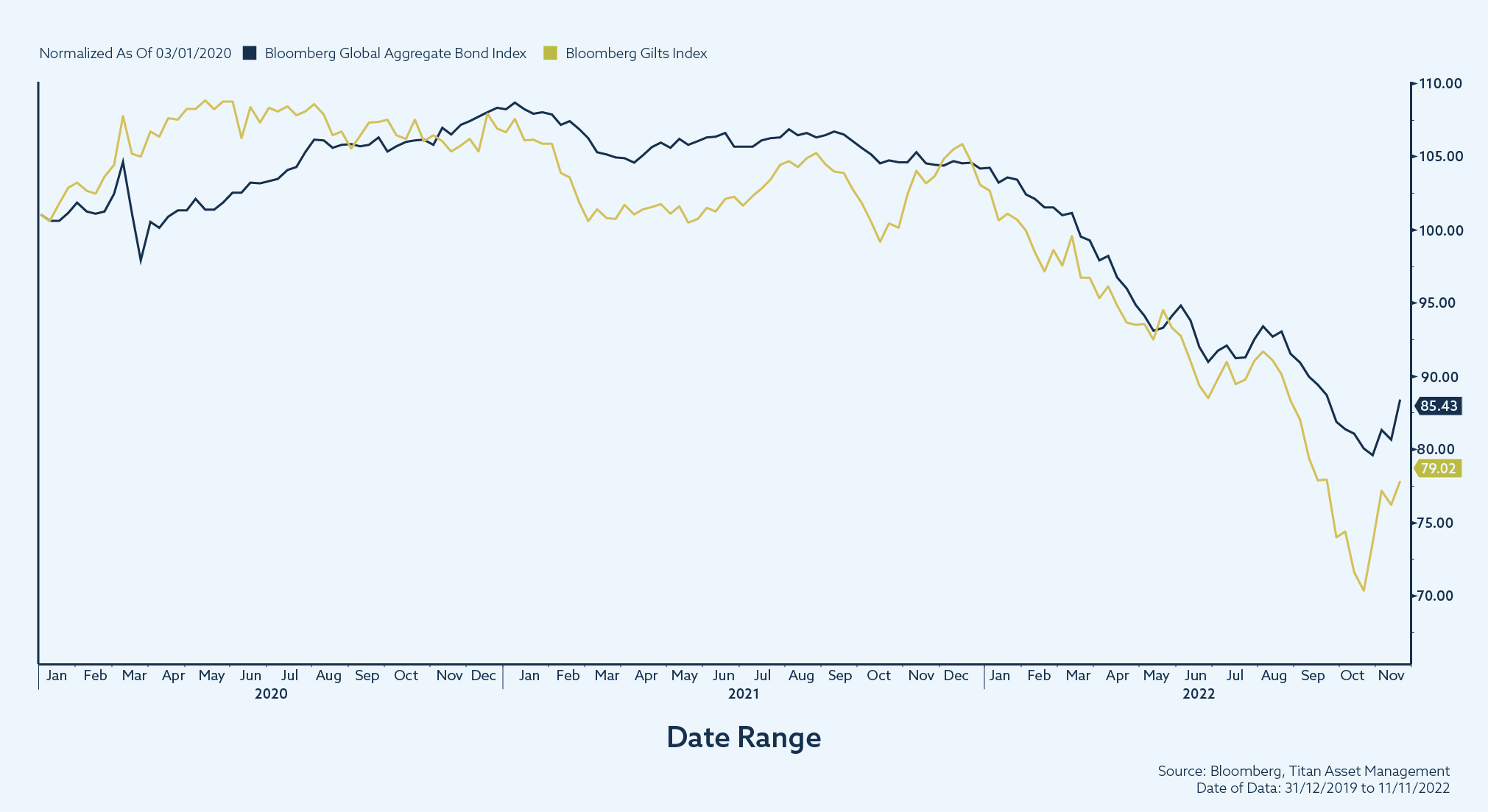

Bonds have had a torrid time of it lately, primarily due to the first meaningful bout of inflation across the world in decades. The Bloomberg Global Aggregate Bond Index, the North Star for most bond investors, has fallen about 20% since the beginning of 2021. The Bloomberg Gilts Index has fallen more than 25%.

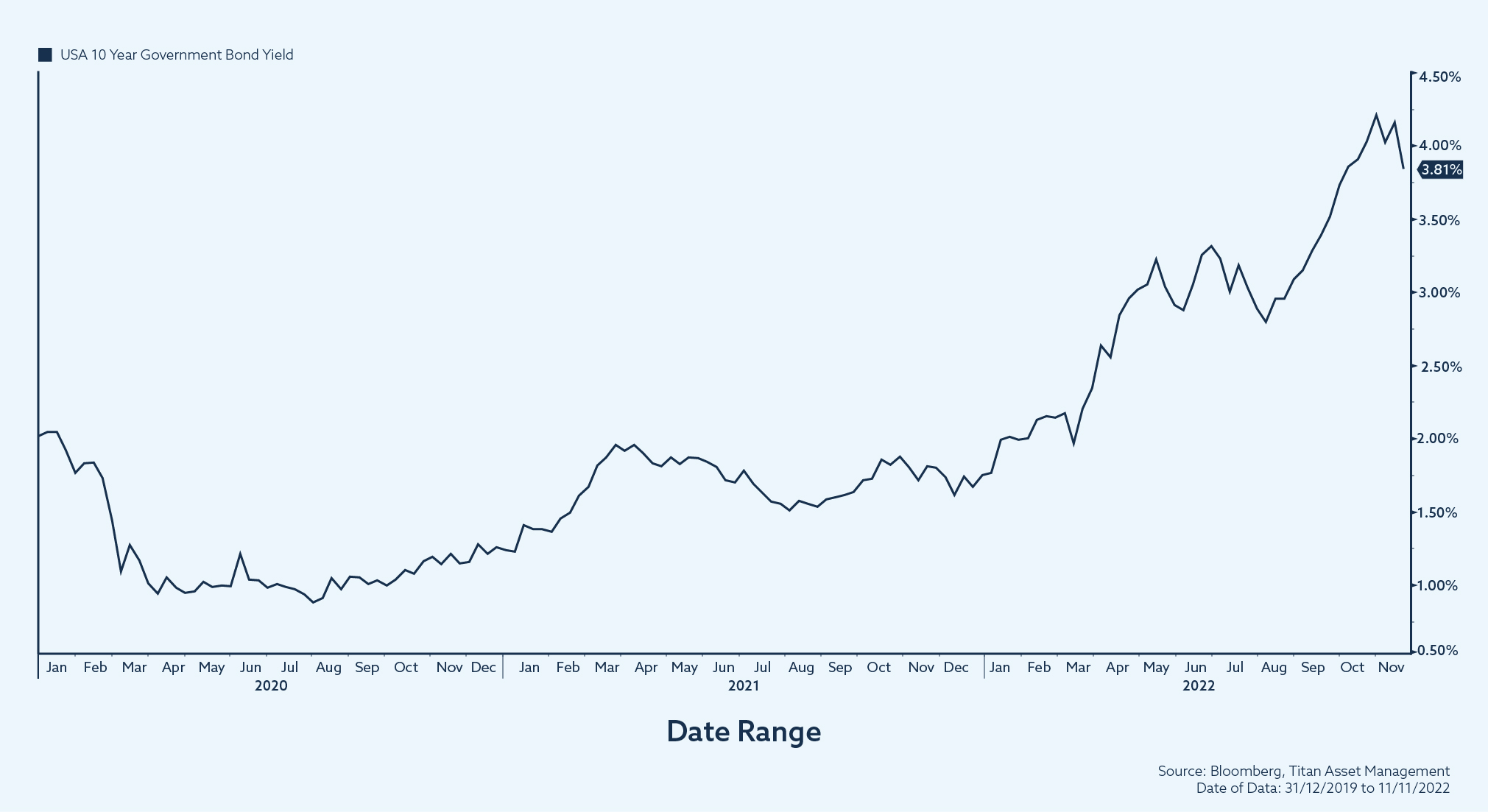

There are 3 market calls that all bond investors must get right: yields, spreads and currency. For much of this bond bear market, the change in yields has been the most impactful of the 3 on bond returns. The yield on the 10-year USA government bond was 1% at the beginning of 2021; it is now almost 4%, reflecting the efforts of the Fed to combat inflation.

Spreads, which measure credit risk, have been less important. In the USA, investors received a premium of about 3% over the risk-free rate to lend to sub-investment grade issuers throughout 2021. Since then, that premium has increased to more than 4.5%. Though not insignificant, this widening pales in comparison to historic blowouts.

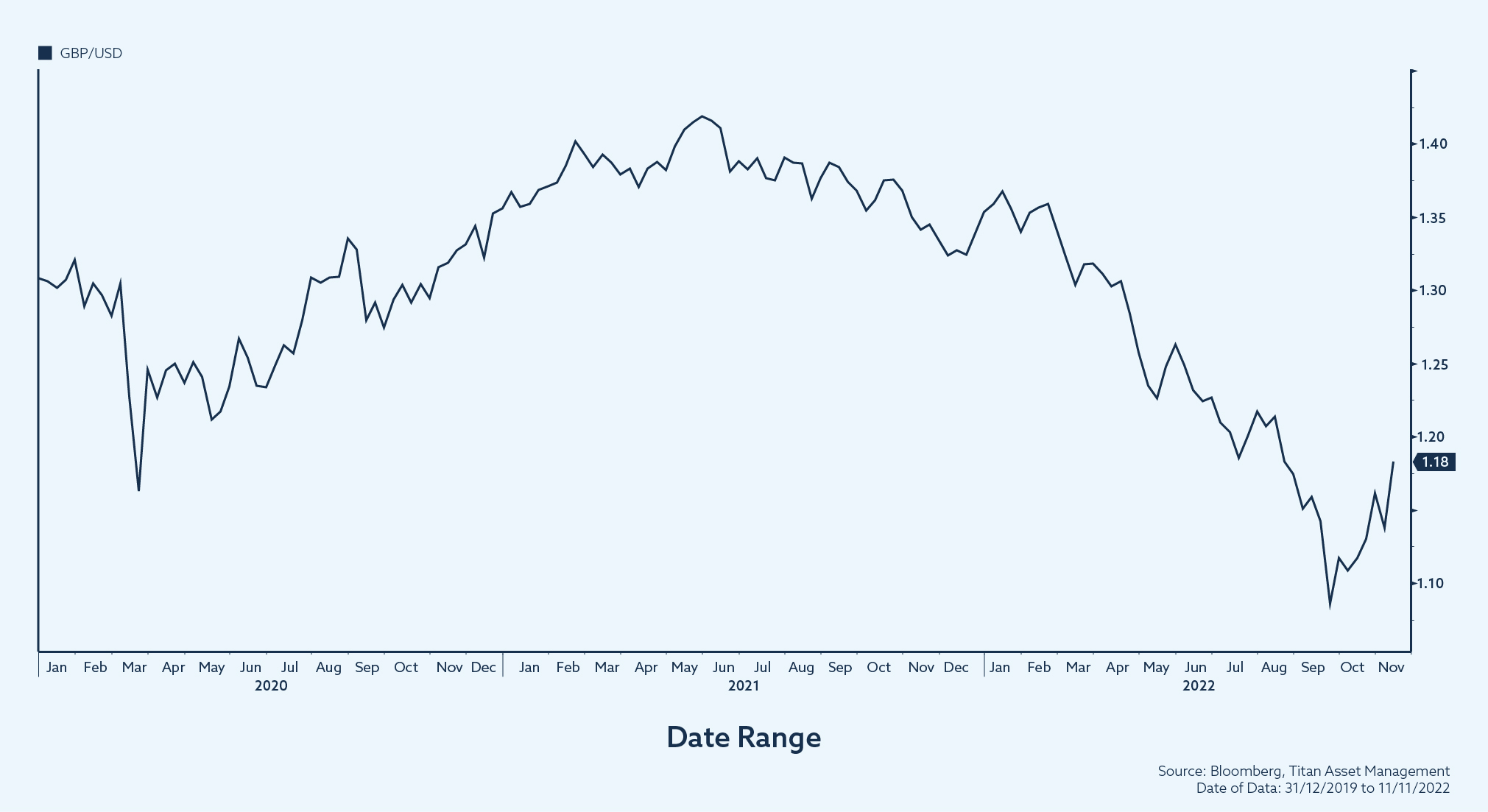

UK-based investors will have felt the effects of the waxing and waning of GBP recently. Cable reached a nadir of 1.16 in mid-2020 before rallying to 1.42 a year later; it has since tumbled back to nearly 1.16. An active approach to currency risk management has been critical to navigate volatility and mitigate any negative effects on bond returns.

Our market calls over the past year have been: underweight interest rate risk (yields), underweight credit risk (spreads) and underweight GBP (currency). We action these market calls across our centralised investment proposition (CIP), which includes a range of funds and a model portfolio service (MPS). We can mostly achieve the same asset allocation across the proposition, but this is not always entirely possible. For example, there tends to be less granularity within asset classes across the lower-cost Passive MPS and we have less control over the actions of external fund managers across the Active MPS. For the ESG MPS, differences arise mainly due to adherence to our ESG investment policy.

The purpose of our ESG investment policy is to separate ESG leaders from laggards, and to exclude certain controversial sectors from our investable universe. Integrating ESG data into our portfolio management processes can effectively identify company-level ESG risks and opportunities.

The task is a trickier one for government bond exposure. For example, in the USA, how should the USD 370 billion of spending on greenhouse gas emissions-cutting measures included in the Inflation Reduction Act be weighed against a USD 700 billion defence budget? How should the USA’s classification as ‘Free’ in the Freedom House Democracy Index be weighed against recent Supreme Court rulings on abortion? These are difficult questions to answer. Most fund managers have found it correspondingly difficult to design an ESG-labelled approach to investing in government bonds.

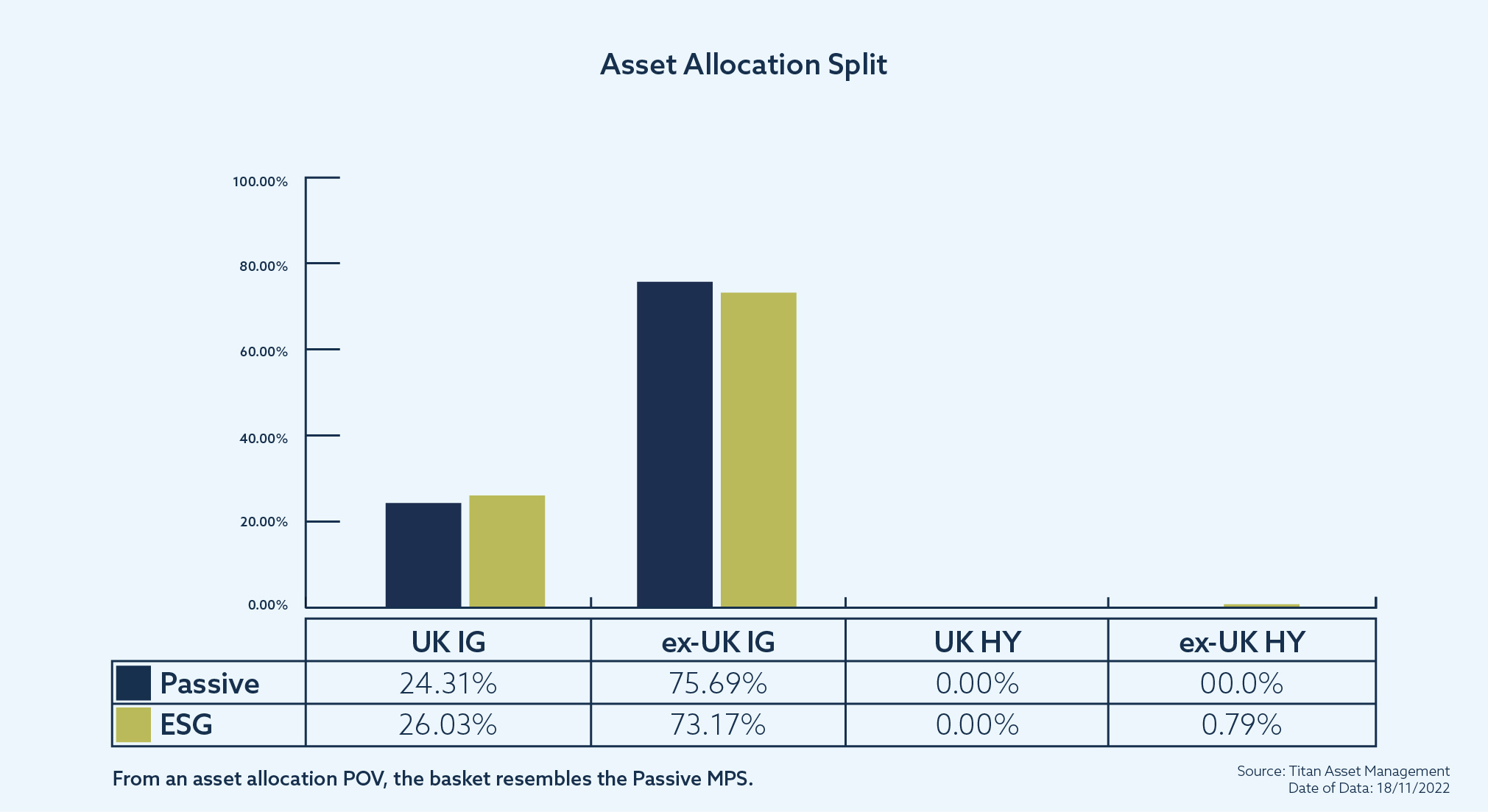

Consequently, for the ESG MPS the investable universe is biased away from government bonds and towards corporate bonds. We have identified only a handful of government bond-majority funds relevant to the ESG MPS, compared to dozens of corporate bond-majority funds.

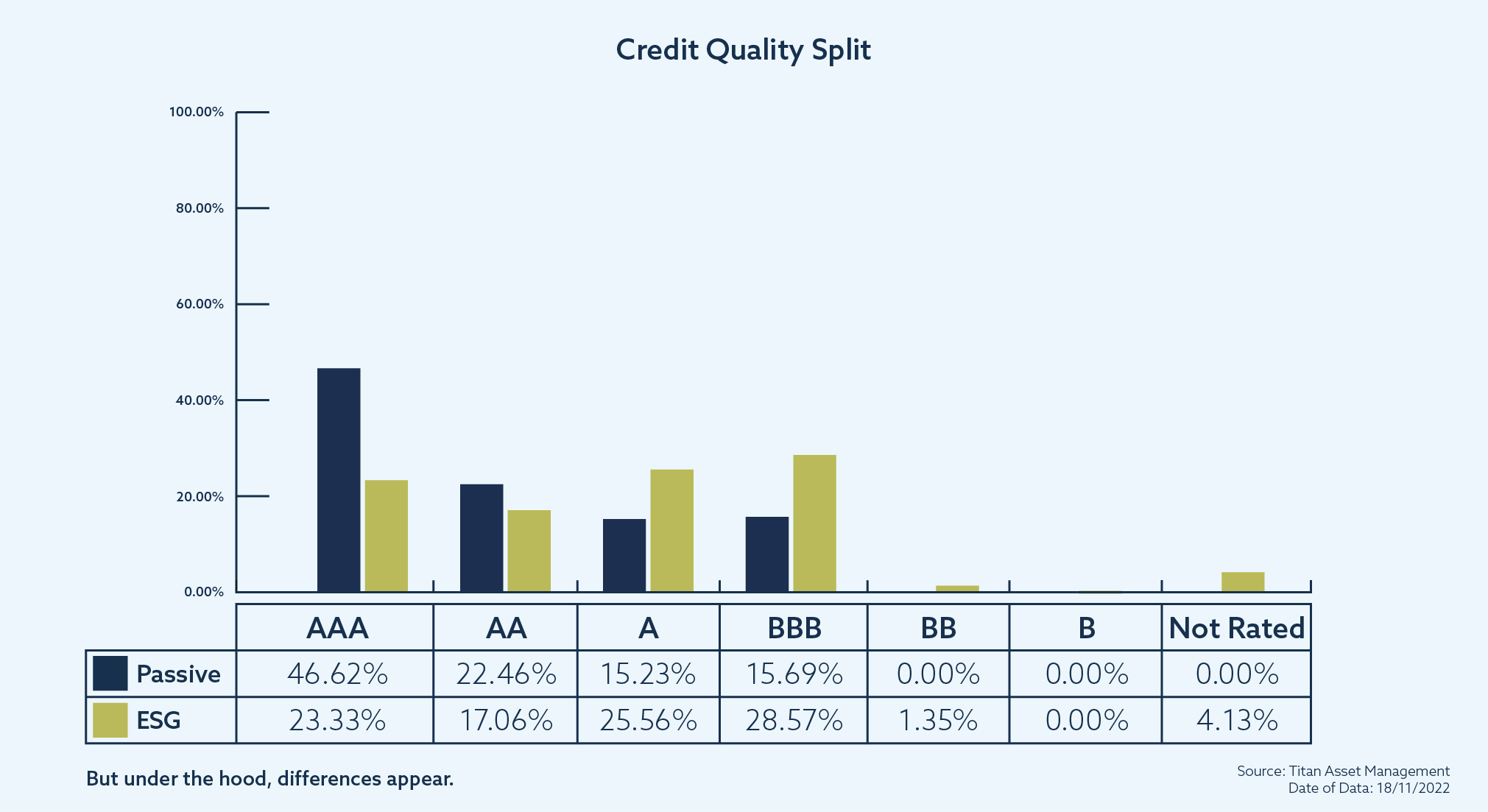

For the ESG MPS, we therefore have to manage our bond basket a little differently to the rest of our CIP. As expected, there is slightly less exposure to government bonds across the ESG MPS. If this difference is a first order effect, there is also a second order effect. Generally speaking, governments are deemed more creditworthy than companies. As there is less exposure to government bonds across the ESG MPS, there is thus less exposure to issuers with better credit ratings. So, the credit quality of the bond basket is lower.

The second order effect is manageable. As we explained, there are multiple levers that we, when thinking about bonds, can adjust: yields, spreads and currency. Due to the credit quality bias, the ESG MPS is more exposed to the downside if credit spreads were to widen than, for example, the Passive MPS. The trick to mitigate this bias is to adjust our exposure to changes in yields and currency, relative to other bits of our CIP.

We can measure our exposure to movements in yields using duration. Compared to the Passive MPS, the ESG MPS has lower duration, which means there is less exposure to the downside if bond yields were to increase (that is, if bond prices were to fall). More, the bond basket of the Passive MPS is fully hedged back to GBP, unlike the ESG MPS which is only 75% hedged. Consequently, the ESG MPS is less exposed to the gyrations of GBP which, in recent months, have been likened to that of an emerging market currency.

It is important to balance the core views of the investment team with the differences in investable universe between different parts of our CIP. Deviations like those discussed throughout this blog, when they occur, can be explained by the idiosyncratic nature of the ESG MPS, and are regularly measured against our core views and asset allocation tolerance thresholds. It is also important to question our assumptions.

If we change our views regarding drivers of risk / return like yield, spreads and currency, we would implement changes to the bond baskets across our CIP. For example, considering how far bond yields have risen recently, combined with a growing recessionary narrative and the possibility that inflation and, thus, interest rates, might soon peak and begin to roll over, we are actively exploring whether or not to increase duration (meaning, interest rate risk) as we head into 2023.